THE

PROJECT

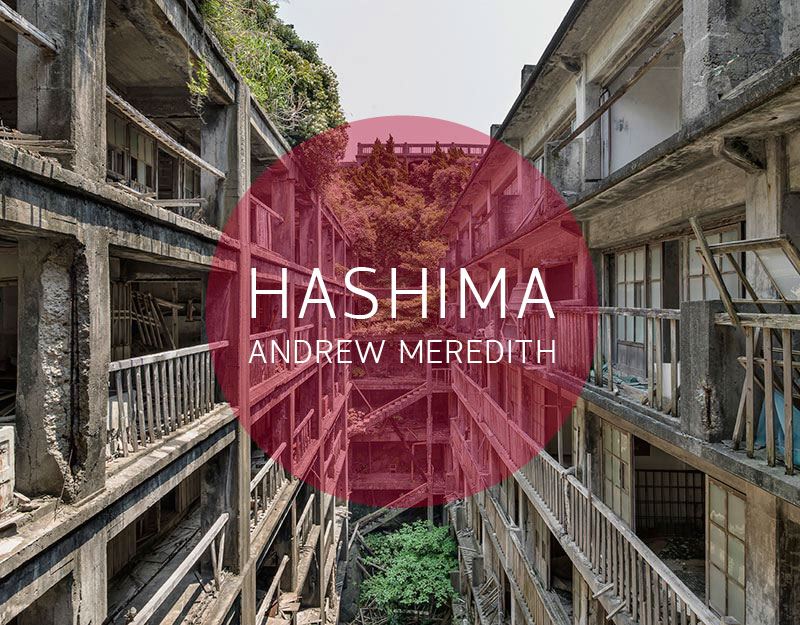

HASHIMA

Photographs by Andrew Meredith

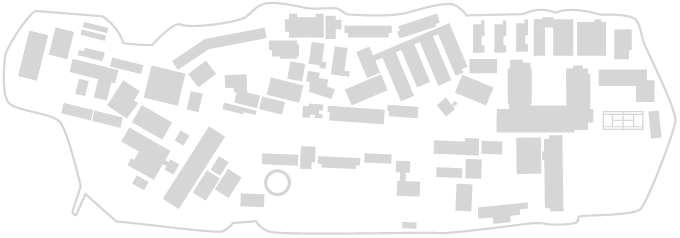

Lying off the coast of Nagasaki on the Southwest coast of Japan, Hashima Island, or Gunkanjima as it's locally known, was once the most densely populated place on earth because of its 15 acre size (the equivalent of 15 football pitches).

In the 1800s, owners Mitsubishi developed the tiny island into a coal mining settlement where coal was dug from beneath the South China Sea. It didn’t take long for the population of the island to grow. This in turn meant that Hashima Island had to expand and improve amenities to accommodate the mining workers and their families, as well as providing education, health care and recreational areas for their children. Hashima's skyline was shaped by the island's tiny size; having no choice but to build upwards, rather than outwards, resulting in a densely packed maze of concrete high-rise structures.

At its peak the island housed in excess of 5,200 inhabitants, all crammed on the tiny island, measuring just 150 x 400 meters. Travel to and from the island was restricted, with the habitants needing express consent from the guards to be able to come and go. This restriction on travel meant all workers needed to live, work on the island itself. As the island's population grew, so did its skyline.

In 1974, the mine was closed by the Government of Nagasaki to protect Mitsubishi’s interests. Oil was now more financially rewarding than coal, leading to a mass exodus from Hashima. Workers and their families relocated to mainland Japan in search of new jobs. In their haste to leave, the people of Hashima Island had no time to pack-up all their belongings, so they had to leave them behind. Today, these items can still be seen in the derelict apartments, school, hospital and playgrounds.

Over many years, Hashima Island remained untouched and was left to decay. Harsh weather conditions including typhoons, high waves and strong winds caused concrete to crumble and wood to rot. Roots of trees caused walkways and corridors to crack and stairwells were blocked by falling debris. There were rumours of ghosts from previous caved in mines, which kept locals from exploring.

The island was closed and considered too dangerous for anyone to step foot on its concrete banks.

On May 1st 2013, we travelled to Hashima to start documenting the island with permission from the Government of Nagasaki.

This project documents what we found.

It was an exciting day that I stumbled upon a website that had images of Hashima. The images showed towering buildings formed from masculine grey concrete, surrounded by rubble and broken bits of wood on what was seemingly a tiny island, built in the middle of nowhere. I instantly became fascinated with this derelict city, knowing immediately that I wanted to photographically document the island and its characteristics. By doing this and revealing some of the island’s history, it would allow me to share Hashima with others to make them aware of its existence, creating images that would encourage curiosity and intrigue.

As a working Architectural Photographer in London, Architecture and the built environment have naturally always fascinated me. The same is said about derelict or destroyed architecture. In everyday life, I am surrounded by pristine modern architecture built by renowned Architects, I think this is why I have long been interested in the built environment at the end of its usable life. I’m fascinated by natural decay, precariously teetering on the edge of collapse, as well as the human story behind the architecture and the people who used to live and work in these spaces.